What is it about human nature that compels us to travel and explore beyond satisfying our physiological needs? For me, the appealing aspects of travel are the same ones that got me interested in design. I love learning about things that I would have never discovered had I not left my own little bubble. Often the benefits of my wanderlust can be applied to other parts of my life, including my profession, and I was about to be enveloped by mascots in branding

I recently took a trip to Japan. I’d done a bit of research and gotten tips from friends who had lived there. Still, nothing could truly prepared me for full immersion into another culture. I loved it right away. Even the things that weirded me out were still fascinating.

Something I noticed immediately but didn’t fully appreciate until later in the trip was how so many ideas in Japanese culture are demonstrated with the use of characters. The abundance of mascots in Japan wasn’t something I was ignorant of before visiting, but seeing it in real-life branding and marketing, effectively and ineffectively, was thought-provoking. In Japan, mascots (yuru-chara) can be used for anything from promoting a product or service to social movements helping tourism and education. If there is an opportunity for a mascot, then there is one, like the purple-flower-wearing mascot of Asahikawa Prison. Their specific brand design is typically unrefined or laid-back (yurui). While they are all supposed to be awkward and kawaii (cute), some cross the line into kimo-kawaii (gross-cute) instead.

Mascots seem to have taken over thanks to a few standouts, like the internationally popular Domo. They’ve become so well liked that there are instances where dozens of mascots are used to represent the same thing, ultimately working against the original goal by watering down brand equity and confusing purchase decisions.

Mascots not only bolster regional pride and education but they can ease the ability to recall the brand. Here I am with a sarubobo doll representing this area of the Japanese Alps.

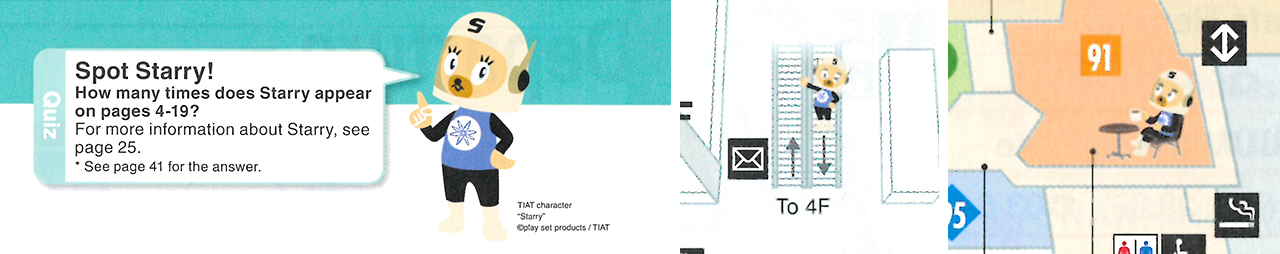

It was so interesting to experience this first hand. It’s not like mascots aren’t used around the world, but the level of celebrity these have achieved got me wondering how this evolved and whether it could reach the same level anywhere else. Some claim Japan had the perfect conditions for creating this mascot boom because its religious beliefs are rooted in polytheism, so the jump to representative mascots wasn’t a large one. What about foreigners without the same background? Clearly this kind of marketing worked on me. I got super into it and really enjoyed picking out different mascots as I found them. The public relations section of the Haneda Airport International Passenger Terminal had its own star-clad, space helmet-wearing mascot called Starry. Starry likes coffee and hates typhoons, and I played “Spot Starry” by counting how many times he appeared throughout the UX of my terminal floor map.

But does Starry really add much to the terminal’s brand? Are enough adults flipping through the terminal map, ticking off how many times Starry is waving to them among the pages? I think so. I myself was tuned into the mania for a short time, and that by itself says something about the mascots’ ability to transcend cultural boundaries. But is it enough, and do they provoke the proper feelings? Seeing a sleepy, possibly drunk airplane mascot for the airport I’m about to fly out of doesn’t give me the greatest sense of ease.

I think it goes to show how important it is to know your audience before executing anything meant to appeal to them. When I’m working with new clients, I learn as much about their services as I possibly can. The more information I get, the better prepared I am to create something impactful that won’t be overlooked, or worse, taken negatively. Designing for the Japanese market would not only require me to understand the product, I would also need to learn all the deep cultural differences that I have no preexisting knowledge of because I grew up in the United States. This can be applied to all matters of design — if you don’t know enough about whom you’re talking to, you can’t reach them. Say you’re designing a website that will be primarily used by senior citizens. Having excellent content that speaks to them is incredibly important, but you also need to understand how they will be viewing and using your website. For example, visually impaired people are still able to use the internet with the help of assistive screen readers, but you must code your website correctly for it to be effective.

So much of what I’ve learned as a designer has been refined through my travels and experiences. I’m not sure I would have ever fully understood the extent of Japan’s mascot affinity and its success in branding without having been part of that world for a short while. Venturing outside of my comfort zone allowed me to see how much of an impact things like culture and even geographical location can make on how you interact with a brand and the way advertising must adjust to meet those variables. It is an excellent reminder of how similar we all are as people. What may seem bizarre to us at first can be made more familiar with a little patience and an open mind.